observations

Simplicity, Earned

Lessons from the Golden Age of Advertising

Simplicity isn’t the absence of thinking.

It’s the result of it.

There was a time when advertising didn’t rush to explain itself. It didn’t panic about attention spans or assume distraction was a character flaw. It didn’t feel the need to entertain first and persuade second. It trusted that if an idea was clear enough—true enough—someone would stay with it.

Some of the most enduring advertisements in history didn’t shout, rush, or explain themselves to exhaustion. They trusted the reader. They trusted the idea. And most of all, they trusted that attention—real attention—had to be earned.

What we now call the Golden Age of Advertising wasn’t defined by a single look or layout. It was defined by discipline. By restraint. By the belief that people were capable of reading, thinking, and deciding for themselves.

And yes—by the advertorial.

The advertorial wasn’t “simple.” It was serious.

Advertorials were not short. They weren’t skimmable. They didn’t rely on bullet points or bite-sized soundbites. And yet, they were some of the most effective advertising ever created.

Why?

Because they respected intelligence.

Advertorials lived beside journalism. They read like essays. They made arguments. They assumed the reader was willing to spend time—if the idea was worth that time.

That’s the part we’ve forgotten.

We didn’t stop writing advertorials because they stopped working. We stopped because we decided—without much evidence—that people wouldn’t read anymore.

That assumption changed everything.

Trusting words didn’t mean ignoring restraint

What’s often misunderstood is this: the Golden Age wasn’t only about long copy. It was about clarity of intent.

The same era that gave us full-page advertorials also produced some of the most minimal, confident ads ever created—ads that said almost nothing and meant everything.

The discipline was the same in both cases.

Say a lot only when the idea requires it.

Say very little only when the idea can carry the weight alone.

Simplicity was never a style. It was a decision.

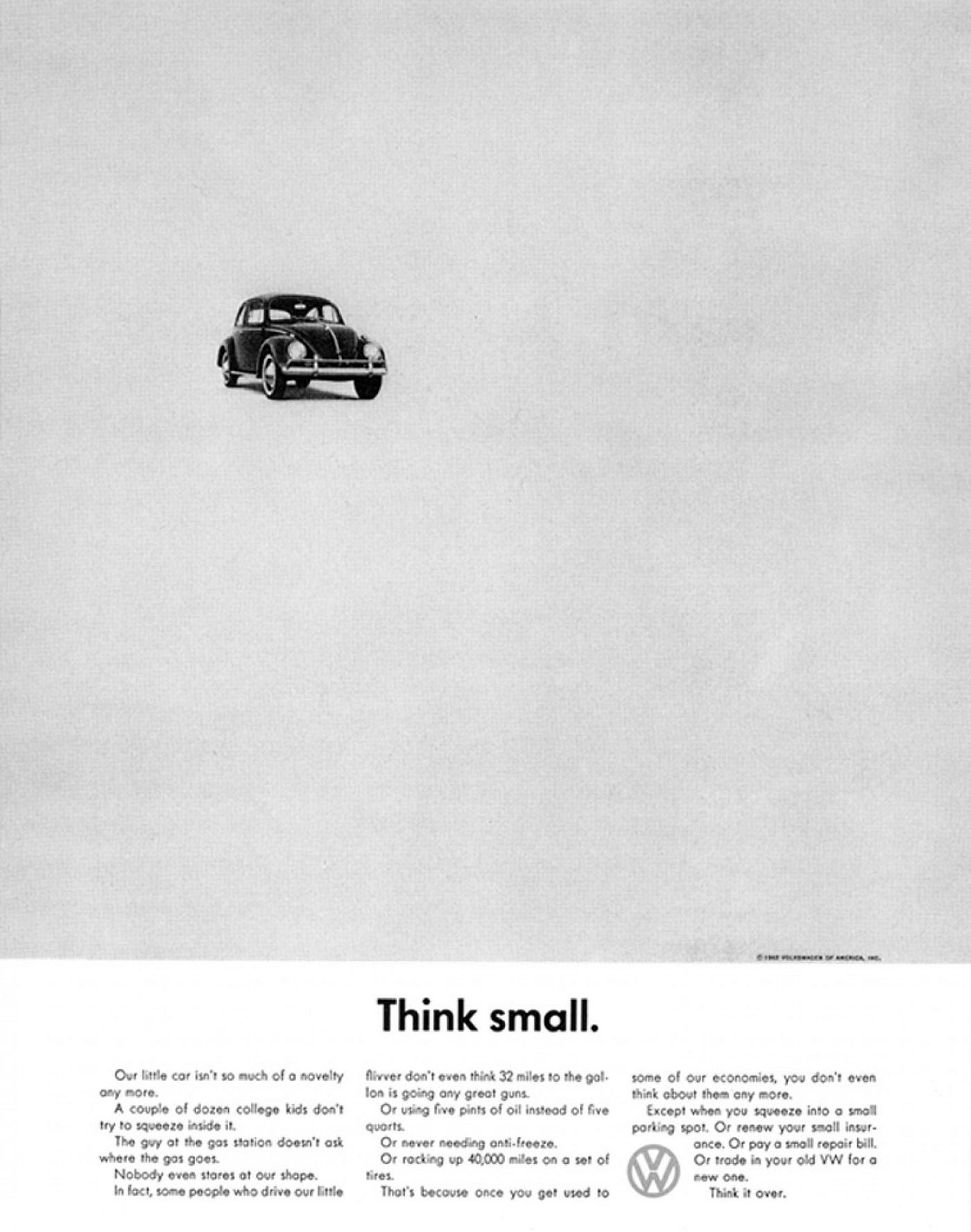

Volkswagen didn’t “write long copy.” They made a case.

The Volkswagen Think Small ad is often praised for its white space and humility. But its real achievement was intellectual honesty.

It didn’t try to turn the Beetle into something it wasn’t. It didn’t hide flaws. It didn’t inflate benefits. It made a calm, logical, human argument—and trusted the reader to follow it.

That’s advertorial thinking, even when the execution looks minimal.

The copy mattered because the idea mattered.

Rolls-Royce proved one detail could do all the work

“At 60 miles an hour the loudest noise in this new Rolls-Royce comes from the electric clock.”

That sentence is an advertorial in miniature.

It doesn’t explain luxury.

It demonstrates it.

One specific, verifiable detail replaced an entire page of claims. The ad assumed the reader could extrapolate meaning—and that assumption made the message more powerful, not less.

Saying less worked here because the thinking underneath was complete.

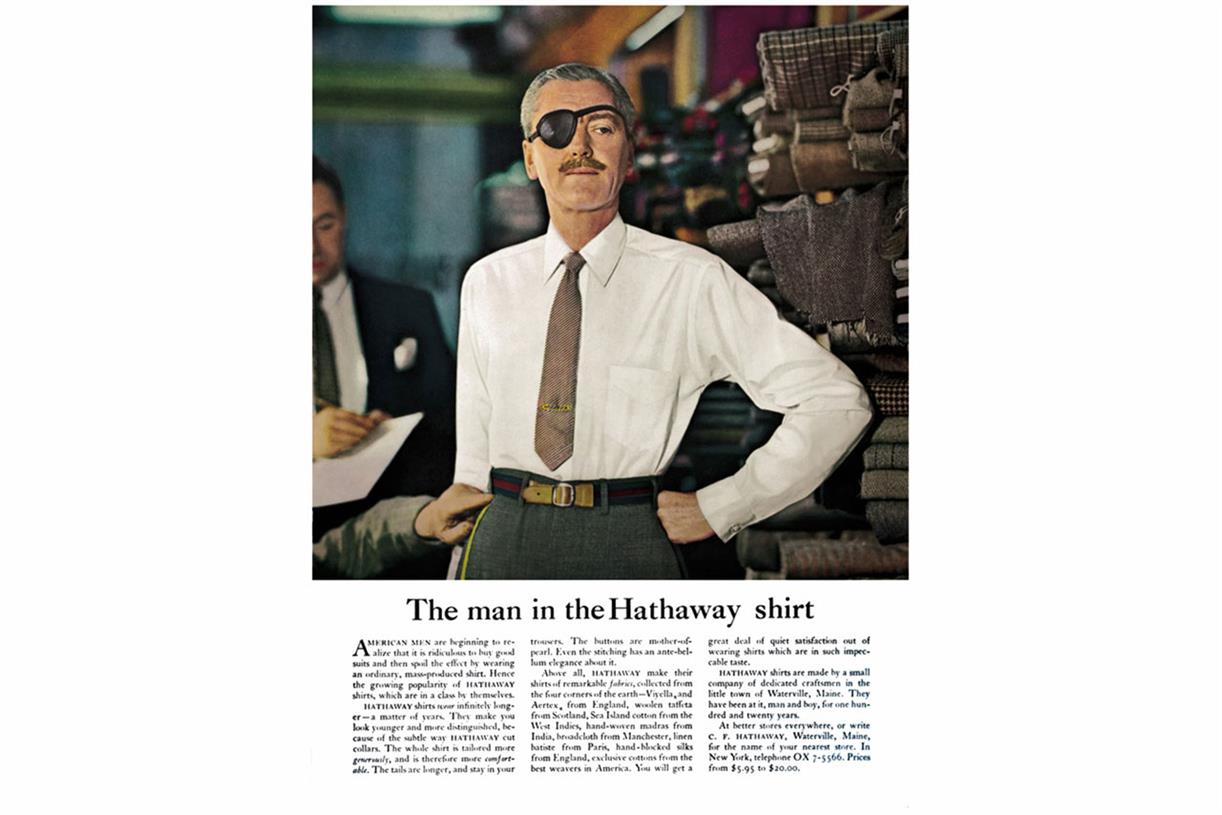

Hathaway showed that mystery is intellectual respect

The man in the Hathaway shirt wore an eyepatch. No backstory. No explanation.

The ad didn’t rush to clarify. It allowed curiosity to do the work.

Mystery is not confusion. When used well, it’s an invitation. And invitations assume the reader can enter on their own.

That’s respect.

What we lost when we assumed people wouldn’t read

Somewhere along the way, we decided that attention spans had collapsed entirely. That people only skim. That everything must be instant, visual, and obvious.

That assumption led to:

over-explaining

excessive bullet points

constant urgency

design doing the talking instead of ideas

Yes, some people skim.

Yes, some ads should be one word or one image.

But not everyone has the attention span of a snail.

The Golden Age understood something we’ve forgotten: audiences are diverse. Some want speed. Some want depth. Great advertising knows when to offer each.

Ten Lessons from the Golden Age (Still True Today)

1. “The consumer isn’t a moron; she’s your wife.” — David Ogilvy

Respect is not optional. When you assume intelligence, your work rises to meet it.

2. “An idea can turn to dust if it isn’t executed.” — Bill Bernbach

Simplicity requires executional courage. One idea means nowhere to hide.

3. “Make it simple. Make it memorable.” — Leo Burnett

Memorability isn’t about noise. It’s about clarity.

4. Long copy isn’t the enemy—bad thinking is.

Advertorials worked because they had something worth saying.

5. One detail beats ten claims.

Specificity persuades better than adjectives ever will.

6. Mystery invites participation.

Explaining everything leaves nothing for the reader to do.

7. Design should serve the idea, not compete with it.

White space is confidence made visible.

8. Saying less works only when the idea is complete.

Minimalism without thinking is emptiness.

9. Not every message needs to be fast.

Some ideas deserve time. Some audiences will give it—if you earn it.

10. Simplicity is the final stage of mastery.

It’s not where you start. It’s where you arrive.

A final thought

The Golden Age wasn’t powerful because it was quiet.

It was powerful because it was deliberate.

It trusted intelligence.

It honored restraint.

It treated advertising as a craft.

Simplicity wasn’t the absence of thinking.

It was the result of it.

Simplicity isn’t the absence of thinking.

It’s the result of it.